This article has been written by John Halle, Acting Big Solar Co-op CEO. Posted as two blogs on the Big Solar Co-op website, January 2023 and June 2023

Part 1 January 2023

We’ve been doing a lot of thinking and research on how we source our solar panels here at Big Solar Co-op and we wanted to share some of our work with you.

The unspoken assumption until recently has been something like this: solar panels are intrinsically a super-green technology because they replace generation which would otherwise come from fossil fuel power plants. The energy used to make them is miniscule compared to that which they produce during their lifetime. There is not much to choose between different panel sources – the differences are around quality, longevity and efficiency.

When we started Sharenergy 12 years ago we felt we were still making the case for solar PV as a serious technology and anything that complicated the narrative didn’t get a lot of attention. It’s fair to say that many solar advocates are more or less still following this logic.

These days solar is no niche pursuit – the global value of the industry is in the hundreds of billions. Like any huge transnational industry it has its dark corners of which we are becoming more aware. As champions of environmental and social justice and active participants in that industry, we have an obligation to understand the issues and act on our findings.

There are two main areas of concern – the carbon footprint of solar panels and the social conditions of their production. For us the crucial question is – are some panels better than others? Which ones? How much better?

In this series of three blog posts we will be examining the issues and possible solutions in more depth. We’ll start with carbon. We call ourselves a carbon-first organisation. Can we walk the talk in our choice of solar panels?

Carbon

Establishing the carbon footprint of solar panels is not a simple business. As a bare minimum you need to consider embodied carbon in manufacturing and transport. There are lots of additional factors as well – the other kit needed to connect panels to rooftops, the ground or the grid, competing uses for rooftops and land, end-of-use impacts. In order to make a comparison you have to understand what other generation you are actually displacing too – in the UK it’s mostly gas, sometimes still coal, but in the future it could potentially be other renewables.

Our research to date suggests that one of the most important differences between panels are the carbon emissions involved in manufacture. There are 4 key stages of solar panel manufacturing. Firstly, polysilicon is made from sand or quartzite. Then it is made into an ingot and sawn into wafers. The wafers are made into solar cells. Finally the cells are assembled into a solar panel.

Two thirds of the energy is consumed in the first two stages so it’s here that the use of clean electricity is most crucial. It comes as a shock therefore to find out what fuel is mostly being used to generate the electricity. Coal.

Coal fuels 62% of the electricity used for solar PV manufacturing

Special Report on Solar PV Supply Chains, International Energy Agency

That’s a damning statistic – coal is one of the very worst fuels from a carbon perspective.

It’s also an average. There’s good reason to believe that solar panels vary very widely in their carbon footprint. At the dirty end, a reported 45% of solar polysilicon comes from the Chinese region of Xinjiang – where electricity is virtually all generated by coal. At the other end of the scale other manufacturers carry out these energy-intensive stages using innovative processes using less energy, or use electricity derived from cleaner sources – gas, or renewables. We estimate that solar panels may vary in their carbon footprint by as much as a factor of 5.

The key word here is ‘estimate’. There is a bewildering lack of reliable data available in the public realm. Given the importance of solar technology in global decarbonisation, you might imagine that rigorous lifecycle analysis was available for any solar panel on the market. At least you’d expect to see the sort of Environmental Product Declarations (EPD) that are used in the building industry and widely available for materials from plasterboard to wall plugs.

Unfortunately these documents are incredibly sparse in the solar industry. Consultancy Wilmott Dixon published a study looking at the carbon footprint of solar in February 2022.

The study depends on EPDs from only 3 manufacturers. The authors weren’t being lazy – most manufacturers simply don’t publish the data. Our own research has only turned up a handful of these documents, and some of those look sparse at best. On the crucial issue of embodied carbon during manufacturing, they generally just point to figures given in official Chinese Government guidelines which are generic rather than specific to that supply chain.

In other words, the carbon footprint of solar panels is not being seen as an important differentiating factor in the wider solar market. That’s quite an astonishing conclusion to us.

From our research so far it looks as if even the ‘dirty’ panels are better than the UK’s current grid average from a net carbon reduction perspective, and therefore much better than generating electricity from gas. But there is clearly an opportunity to maximise carbon savings by choosing the greenest solar panels. The impact of that choice is hard to quantify but it could easily amount to a doubling of decarbonisation, which would be enormous.

In the absence of hard data, how do we make a choice?

One approach is to look for manufacturers who have committed to power their operations with 100% renewable energy. Giants like Longi and Jinko appear on the high-powered RE100 global corporate renewable energy initiative list alongside Apple and Google. That looks exciting but we’re treating this with some caution. Firstly, these are future commitments rather than current reality. Longi are aiming for 100% renewables by 2028. How close are they to this now? The list does not say. We’re also bearing in mind that these solar manufacturers don’t actually make the whole solar panel from beginning to end. A manufacturer of solar panels could legitimately claim to power ‘their operations’ from 100% renewable energy sources but be buying their polysilicon from a supplier largely powered by coal.

The approach we are taking is instead to seek to source panels from manufacturers who are showing leadership on the sourcing problem matched with real quantifiable progress. Our first panels will come from Meyer Burger. After many years making solar manufacturing equipment for others, Meyer Burger started their own production in 2021. Their modules are produced in Germany using 100% renewable energy. Their polysilicon is sourced from Germany and Norway.

These panels are very high quality and around 20% more expensive than comparable products. They do have a very low degradation rate which over time compensates for much of the added cost, but here at the Big Solar Co-op we are taking a conscious decision to pay more for panels which we believe have a significantly lower carbon footprint.

There are a number of other reasons to support European-made panels. Reduced transport emissions are an obvious plus. However for us the big one is the set of social issues around the production of panels, from basic worker rights up to serious human rights concerns.

We will be examining these issues in more depth in the next blog post in this series. The third blog will examine some of the more creative ways we are looking to reduce our environmental and social impact even further.

Part 2 June 2023

In my first blog post of this series I took a look at the carbon implications of solar panel manufacture. Not all solar panels are the same – some have a much larger carbon footprint due to the way they are manufactured. This goes way back up the supply chain to the extent that the way the actual solar module factory runs is almost irrelevant in the overall picture – the dirty stuff happens at the raw materials end. Unfortunately that is exactly the part of the process where facts are hardest to come by, making carbon footprinting of solar panels an impossible task – at least for us as buyers.

In this blog post I’ll be looking at the parallel issue of human rights in the solar supply chain.

A landmark report

In 2021, two researchers at Sheffield Hallam University named Laura T. Murphy and Nyrola Elimä published a report called In Broad Daylight. It’s a remarkable piece of work, combining academic study with extensive fieldwork under difficult conditions, and its findings are devastating. The report focuses on the solar industry’s links to the practice of ‘labour transfer’ affecting indigenous Uyghur and Kazakh people in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. The researchers say:

“…labour transfers are deployed in the Uyghur Region within an environment of unprecedented coercion, undergirded by the constant threat of re-education and internment. Many indigenous workers are unable to refuse or walk away from these jobs, and thus the programmes are tantamount to forcible transfer of populations and enslavement.”

That word – enslavement. Reading the report I felt its finger pointing straight at me. Like many people in the UK over the last few years I have become ever more aware of the degree to which our prosperity as a nation has depended on slavery. It’s a crucial reckoning which we have yet to properly undertake as a society. But this was direct and personal. I was buying these products of slavery, and most of my waking hours were spent persuading others to buy them too.

It’s curious how solar has managed to sidestep the scrutiny we are now well-used to giving other things. I worked on the timber supply chain in the early days of the FSC. I was an enthusiastic early adopter of the Fairphone. I’ve been drinking Fairtrade coffee since I was a student – and it was absolutely horrible back then! But I had never really considered the solar supply chain in the same way. Solar was high-tech, probably made in Germany, and the challenge was simply to get more of it built.

That complacency was completely turned upside down by Murphy and Elimä’s report. Over the last decade, the core solar industry has almost completely moved to China. There are still module manufacturers in the EU and US, but the heavy industries of quartzite mining, polysilicon production and wafer sawing are dominated by China.

The report lays out the core reasons this is a problem:

- 95% of solar modules rely on one primary material – solar-grade polysilicon.

- Polysilicon manufacturers in the Uyghur Region account for approximately 45% of the world’s solar-grade polysilicon supply.

- All polysilicon manufacturers in the Uyghur Region have reported their participation in labour transfer programmes and/or are supplied by raw materials companies that have.

- In 2020, China produced an additional 30% of the world’s polysilicon on top of that produced in the Uyghur Region, a significant proportion of which may be affected by forced labour in the Uyghur Region as well.

The stunning thing about this is the scale of the issue. The report goes on to look at many of the leading ‘Tier 1’ manufacturers of solar panels – brands that are familiar to anybody installing solar in the UK – and charts their relationship with forced labour in Xinjiang. Some manufacturers show every sign of being directly involved, with solar production facilities even being co-located with detention centres. But almost every solar manufacturer buys their polysilicon or wafers on the open market. This means they are almost certainly buying raw materials which are at least in part the result of enslavement without necessarily knowing the extent of it themselves.

This is a picture of a supply chain which has gone completely off the rails when it comes to the most basic ethical standards. More concerningly, there is little to no transparency – the basic building block of ethical procurement.

The solar industry responds

The response to Murphy and Elimä’s report from within the solar industry has been considerable, with several new initiatives coming forward. A number of UK developers have signed up to the Solar Energy UK statement which states:

We, members of the UK solar energy industry, condemn and oppose any abuse of human rights, including forced labour, anywhere in the global supply chain. We support applying the highest possible levels of transparency and sustainability throughout the value chain, and commit to the development of an industry-led traceability protocol to help to ensure our supply chain is free of human rights abuses

This is good – it shows the widespread concern which goes well beyond our community energy movement. Signatories include the largest UK solar developers with portfolios worth billions.

Notably missing from the mix, however, are any of the main solar panel manufacturers. We do have to ask ourselves why that is. Do they not consider this issue to be important? It seems to me more likely that they are so heavily invested in the dominant supply chain that right now they don’t have a leg to stand on. In other words, they are hiding.

It’s instructive to look at the kind of statements put out by manufacturers who have broken cover on the issue. For example, see the human rights statement made by Photowatt, a relatively low-volume German solar manufacturer. They say:

We are competing in a system of free trade. So free, that products that are imported into our European area don’t have any obligation to comply to the same social standards that we impose on ourselves, and for which we pay taxes and many other costs that relate to the way we have built up our society and its related values. The more one moves away from these standards, the cheaper products get. The farther away, the more difficult it is to check. Obviously, that doesn’t only apply to the solar industry.

That’s admirably candid, but it effectively amounts to an admission that they have lost control over their supply chain. And these are the good guys – at least they are saying something! An alternative approach is the blanket statement such as that produced by Eurener, another European module manufacturer, which consists of one single line:

Eurener EEW states that the modules produces in our factories categorically exclude the use of raw materials from suppliers in the Xinjiang region in its supply chain.

That’s great – but we can be forgiven for wanting a little more context or evidence. Note that these statements are found on the websites of UK solar distributors who have been passing on customer pressure to their suppliers – they are not being volunteered by the suppliers, and don’t seem to appear on their own websites.

Why so coy? Given what we know about the supply chain it seems likely that in many cases there is nothing good to say. Even a supplier that is making positive steps may be unlikely to come forward because it would involve also admitting how bad things are overall.

In some cases manufacturers say they consider their supply chain information to be so commercially sensitive that they cannot expose it to public view. That may be true, but it is not a great argument, given that this problem can be easily solved by allowing a credible but confidential third-party supply chain audit. It seems incredible but we have not yet seen solar panels in the UK market which have any sort of robust audit coverage. I would love to be wrong about this but we’ve been looking quite hard for several years.

Community energy

The response from within the community energy movement has been quite interesting. We have been in contact with many of our fellow solar co-operatives who care deeply about these issues, and we’re working together as part of the Community Energy England Ethical Sourcing working group. At the same time we’ve faced quite a lot of pushback. Understandably, hard-pressed community energy activists are not keen on having yet another set of challenges to deal with!

Some feel that we are so small that we cannot make a difference. I can’t agree with that. The community energy movement has always managed to have more influence and power than its raw statistics would imply. Moreover, many voices in the industry are effectively silenced by complicity. I argue that our role is to take the lead however and wherever we can.

Another angle I’ve heard more than once goes like this: climate change is a challenge for the whole world. If we build less solar because ethical solar is too expensive or hard to source, we are short-changing everybody, including even those belonging to the affected minorities in China. That’s one of those arguments that sounds reasonable for the first few minutes and goes downhill from there. It ends up being uncomfortably reminiscent of the defences of slavery put forward in the early nineteenth century.

Is it true that we must tolerate human rights abuses in order to decarbonise? No, of course it isn’t! Our transition to a post-carbon economy must be a just transition. There is not much point in preserving humanity if in doing so we debase ourselves.

Looking for solutions

So, what can we actually do?

It’s become almost second nature now in the UK to look overseas and see if other countries have found solutions while we have been slowly waking up to the problem. On this issue, it is perhaps surprising that leadership is being seen most strongly from the USA. The Biden administration passed a bill in 2021 banning imports from Xinjiang, which has led to seizure of over 1000 shipments of solar equipment, reportedly including panels made by world-leading companies. This initiative should be seen alongside the Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022, which contains provisions for very significant tax breaks for domestic production of solar.

The response from manufacturers has been a steady stream of announcements of new solar capacity in the US – not just module assembly but vertically-integrated manufacturing at all stages of the supply chain. Of course, protectionism is nothing new in international trade. But this development offers the opportunity for US-based solar developers to source panels which are demonstrably free from the human rights abuses documented in Murphy and Elimä’s report. It has also ushered in a change in culture. At a recent event organised by sustainable business consultants Action Sustainability I spoke to an American representative of a solar manufacturer who said “this is part of our everyday work now”. She was surprised and shocked by the lack of action in the UK.

The US legislation looks to have also forced a re-think for some solar manufacturers who are staying in Asia but are changing their sourcing policies. We’ve seen a number of announcements of new solar capacity in other parts of China – notably in Qinghai, the province to the southeast of Xinjiang. While this may help to work around import restrictions, it’s not clear if it will actually improve the human rights situation. Qinghai does not have many Uyghurs, but it does have many other ethnic minorities, estimated at 45% of the province’s population and including Tibetans, Hui and others. I have seen the Chinese occupation of Tibet and witnessed human rights violations first-hand – there is ample evidence that this is ongoing.

All this negativity towards China can easily be misinterpreted as xenophobia. Of course there is nothing wrong per se in buying solar panels from China. It could be argued that China has played a very important role in enabling the solar revolution by bringing prices down, and many Chinese manufacturers make high quality products with a deserved global reputation. Across a large and complex economy it’s likely that some Chinese solar supply chains are better than others, and some may already be ready for ethical scrutiny.

The key problem is that even if this were to be the case, the Chinese state effectively prohibits independent assessment. Intriguingly, it does not seem that labour costs are a very significant factor in the Chinese advantage – it follows that the Chinese solar industry could still be very competitive even if forced labour practices were entirely eradicated. There is some hope that pressure from global markets will force change, though we also need to be able to reliably know when this has happened.

The European solar industry

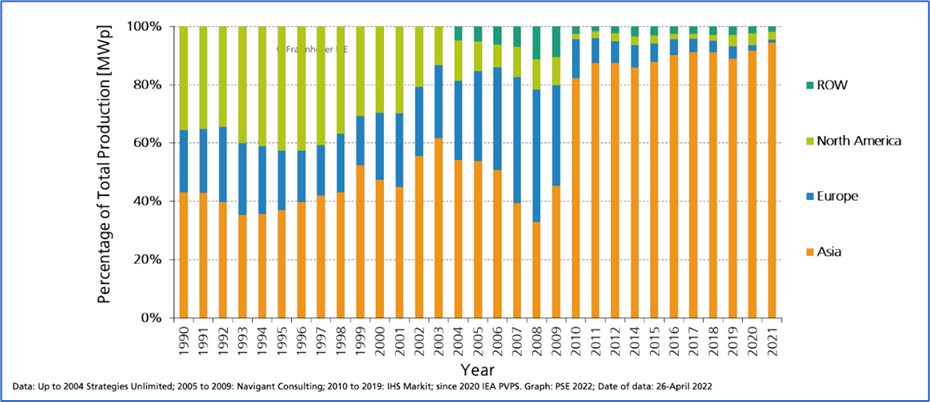

Across the Atlantic, there is movement within the EU. Until quite recently Europe was a major player in worldwide PV production, but over the last 15 years this has eroded almost completely.

Source: Fraunhofer Institute

Simply put, China has managed to produce solar panels of high quality at lower cost than Europe. Europe’s own protectionist measures in the form of so-called anti-dumping legislation from 2013 to 2018 had little effect in stemming the flow.

Now we are seeing renewed calls within the EU for measures to stimulate EU solar manufacture. The EU’s answer to the US Inflation Reduction Act is the Net Zero Industry Act. Rather than focusing on financial incentives, this looks to build the market in other ways, by supporting markets and enhancing skills. The Act has received lukewarm support at best: economic thinktank Bruegel acidly commented:

Those who oppose the proposal will possibly be relieved when they understand that it will cost nothing and achieve nothing

Nevertheless there is something of a quiet renaissance of solar in the EU. This is supported by a number of factors – increased transport costs reduce the cost advantage of Asian solar, as do increasing living standards and wages in China. Geopolitical upheavals, particularly Russia’s war in Ukraine, have focused European minds on the importance of controlling energy and its means of production.

This has opened a rather narrow window for us, as a small solar co-operative, to source our solar panels from this newly-emergent European solar sector. Of course, it is not enough for panels to be manufactured in the EU – we also need to see evidence that the whole supply chain is ethically sourced. That narrows down the options considerably. Research from the Fraunhofer Institute shows how few upstream facilities there are in Europe:

There are only four wafer manufacturers, and five polysilicon producers (not all of which are currently operational). Of these only Wacker is a large player internationally, as the 5th largest solar polysilicon producer globally.

Our choice

At the moment the Big Solar Co-op has decided to use solar panels from Meyer Burger. They are a Swiss company, manufacturing in Germany but more crucially sourcing significant proportions of their raw materials from European sources, having signed supply agreements with Wacker, Norwegian Crystals and Norsun. They further state that the balance of their polysilicon comes from South Korea.

Meyer Burger have been supplying solar panel-making equipment to others for over 30 years before entering the manufacturing market themselves in 2021. Our panels are sourced via our distributor Wind and Sun who have been going even longer and who have fully supported us in our ethical sourcing journey. Even with their help we have had to piece together the evidence to make our decision – as with all the other manufacturers we have examined, no independent supply chain audits are available.

It was not an easy decision to make. Meyer Burger panels are considerably more expensive than competitors – up to 30% more expensive than mid-market panels with broadly similar specifications. One saving grace is that they are very high quality, with excellent long-term warranties, low annual degradation rates, and good performance in lower light. This means that over time the impact of the high capital cost is not quite as severe. However our decision still entails a significant financial penalty.

Is it worth it? We think so. Of course our relatively small volumes of panels are not going to change the world on their own. Some people have told us that we are wasting our time – the panels we are not buying are just going to others anyway. That’s a bit like the argument that you might as well get on a plane because it’s going with or without you – it ignores the fact that if you can persuade others not to fly then sooner or later the planes stop.

In 1862, in a meeting at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, Lancashire cotton workers agreed to maintain an embargo against cotton picked by enslaved people in the US. The decision was made at great personal cost for many of them who lost their livelihood and faced destitution. Yet ultimately the embargo was credited by Lincoln as one of the factors leading to the overthrow of slavery in the US.

More prosaically I keep thinking of that first disgusting cup of student Fairtrade coffee – and the fact that 25% of all coffee sold in the UK is now Fairtrade (and tastes pretty good). To make change happen, you have to start somewhere, and this is where we choose to start with ethical solar.

In the next blog I’ll be looking forward to what else we can do to push forward the ethical solar agenda and reporting on our progress – including some unusual and innovative approaches that we are trying out.